|

| Credit: xkcd |

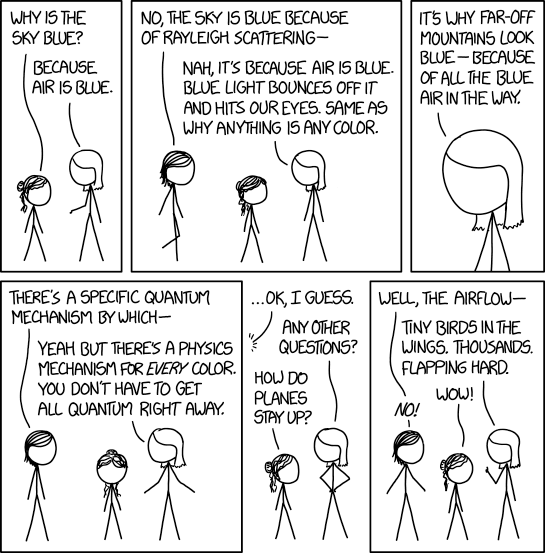

I agree with this argument on one level, and one of the reasons I mentioned the sky's blueness in discussion is because it's an example of one of the three broad reasons why an object is a particular color (reflection/absorption, spectral lines, and thermal radiation). But I also mentioned the blue of the sky because Rayleigh scattering is interesting in a couple ways.

First of all, one way to think about the color of the sky is instead to think about the color of the sun. Sunlight is white (composed of all the colors in the visible spectrum), yet the sun is yellow. Why? Because Rayleigh scattering scatters some wavelengths (blue) more than others (red). The result is that wherever you look, you're looking at the sun; it just depends on whether or not the sun's photons had to bounce around a few times before they got to your eyes (and consequently look like they're coming from somewhere other than the sun).

The second reason I brought up Rayleigh scattering is that, for most objects that are a particular color by dint of reflection, the explanation for why is both complicated (a specific configuration of quantum mechanical energy levels) an unilluminating (it just worked out that way). By contrast, Rayleigh scattering is one of the few instances where the explanation is fairly simple and clear. We can see the process at work throughout the day. Shorter wavelengths of light scatter away as they pass through air. The more air they pass through, the more they scatter. This is why sunsets and sunrises are particularly red: the sunlight is moving through more atmosphere (because the sun is not just straight up), and the blue light has a lot of opportunities to get lost along the way.

But ultimately, xkcd is right that blue is just the color of air, as long as we want to think of color as a property of an object. And why wouldn't we? Well, we can engage in some fun-sucking reductionism by pointing out there is no blueness contained within air, just as there is no greenness contained within leaves. Color arises out of an object's interaction with light and eyes, and it just so happens that a particular interaction involving the sky produces blue. Many philosophers will want to push back against this kind of reductionism by saying, well, okay, then that's just what we mean by the property of blueness: being so configured that interaction with light and eyes produces the subjective experience of blue.

This is a common theme in analytic philosophy. Science has a tendency to unravel our everyday notions by telling us things like, no, we don't really ever touch an object; it's just the electric forces of our skin interacting with the electric forces of the couch. But philosophers balk at this by arguing that we clearly successfully communicate something when we say that, for example, humans have touched the surface of the moon. So let it be that what touching really means is... you get the idea.

But then what does it really mean to say that an object is blue, if blueness is a property that arises only through interaction? Well let's do a little thought experiment. Imagine that one of those TRAPPIST-1 worlds—tidally locked into its orbit around a cool red dwarf—has an atmosphere just like ours. On tidally locked worlds, the sun never rises or sets. One half of the planet is always facing the sun, while the other half never sees it. This could lead to a situation (although an atmosphere probably helps to mitigate it) where one half is a blasted hell hole and the other is a frozen wasteland. Consequently, many scientists and SF authors have imagined life arising only in a narrow strip of twilight at the terminator between night and day. There, the temperature might be just right for life. With a cool red sun (meaning much less blue light to start with) always on the horizon, a sky such as ours might always be some shade of red.

|

| Credit: ESO |

Let's go a step further. Say that the general lack of short wavelength light means that these aliens' eyes never evolved sensitivity to blue light at all. Again, they could perform experiments and develop a theory of optics, but there's no situation in which they would describe the sky as blue, because they have no concept of blue at all.

However, blue-seeing humans are only 40 light years away, so we might someday travel there and explain the reality to them. We might say, your sky looks red, but that is only an illusion. If your eyes were sensitive to short wavelength light, and your planet were not tidally locked, and your star were luminous enough to shine brightly across the specific range of 400-700 nanometers, then you'd see that in reality your sky is, in fact, blue. The aliens would twirl their fuzzy tentacles in derision and laughter, as aliens are wont to do.

Now you might object here and say that we have plenty of names for things we don't have direct subjective experience of. For example, we've labeled the rest of the electromagnetic spectrum, from gamma rays on up to radio waves, even though we only have access to a tiny bit of that spectrum. And that's true enough, but we wouldn't say that the color of an object is x-ray. There might be some property there, but it's not color.

Okay, but let's turn the tables around here. Maybe TRAPPIST aliens are sensitive to infrared light and have a whole host of specific names for the wavelengths they subjectively experience in that range. That sounds a lot like color, too, and it seems anthropocentric of us to deny them their infrared colors. So we can say that blue is a human (or Earth creature) color and that an object is that color when it reflects light in a particular range of wavelengths. That's what color is: the subjective experience of a particular wavelength of light.

But then the aliens might ask, so what's the wavelength of this "brown" color you humans are always talking about? Brown does not have a wavelength; it doesn't show up in the rainbow. Brown is a color humans experience because our perception of color is based on more than just wavelength; it also includes contrast levels and overall brightness. Brown only shows up when something with a red or yellow wavelength is dim compared to what’s next to it.

Purple, too, is not a "real" color by the rough definition given above. It is not composed of a single wavelength but multiple wavelengths that our brains interpret as a single color. Why? Because we don't actually have perfect, exact wavelength detectors in our eyes. Instead, we have three different kinds of cones (photoreceptor cells) that absorb light in three ranges of wavelengths that overlap a bit.

|

| Credit: Vanessaezekowitz at Wikipedia |

So what do we say when the aliens ask what it means for something to be purple? Oh, an object is purple when it reflects both short wavelength and long wavelength visible light in a situation where creatures evolved to pick out that combination as signifying something distinctive. Ah, yes, of course.

All of this is not to say that there's no such thing as color, or that trees aren't brown. Again, it does no one any good to object to every statement about the color of an object by saying, "Well actually, leaves absorb everything but green!" So yes, the sky is blue because air is blue. That is a perfectly fine answer that conveys an important aspect of what color is all about. But that important aspect might not be that color depends on reflection; rather, it might be that the idiosyncratic history of our sun, our planet, and our species have led to the subjective experience of color.